Ghirlanda di foglie finte, 25,6 m, decorazione di foglie di edera artificiale, per la decorazione della casa, interni ed esterni (foglie di scindapso/12 fili) : Amazon.it: Casa e cucina

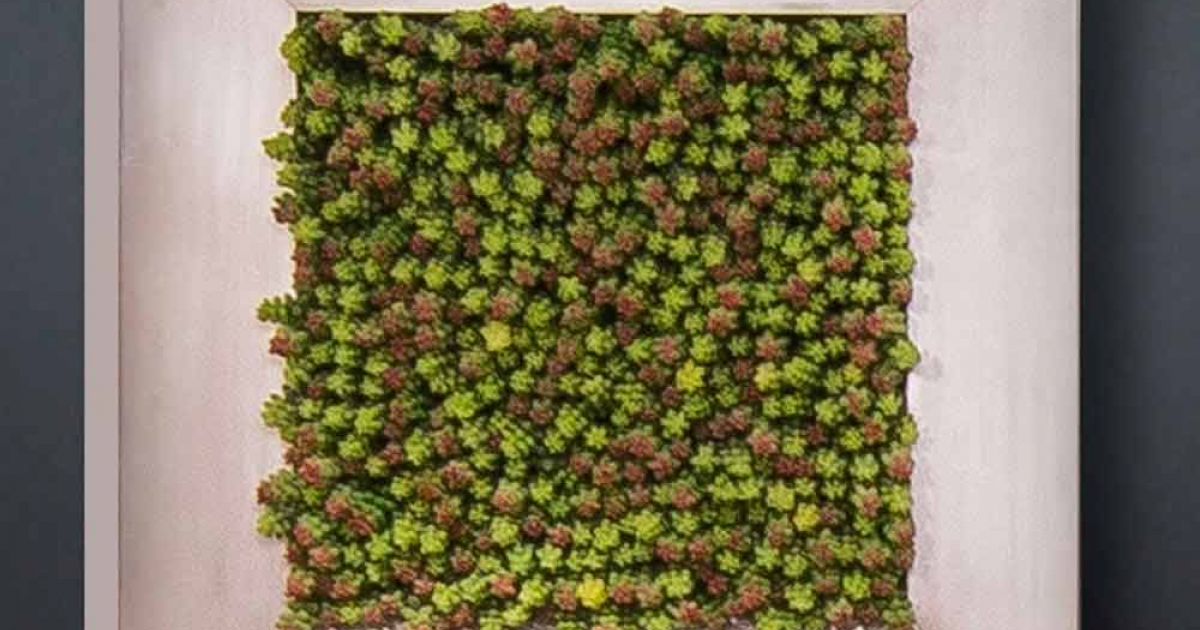

Piante Artificiali e Finte e Giardini Verticali Artificiali di spettacolare Qualità - Milano - Roma - Piante ed Alberi Artificiali di ALTISSIMO LIVELLO | StoreBM a Milano Roma Napoli

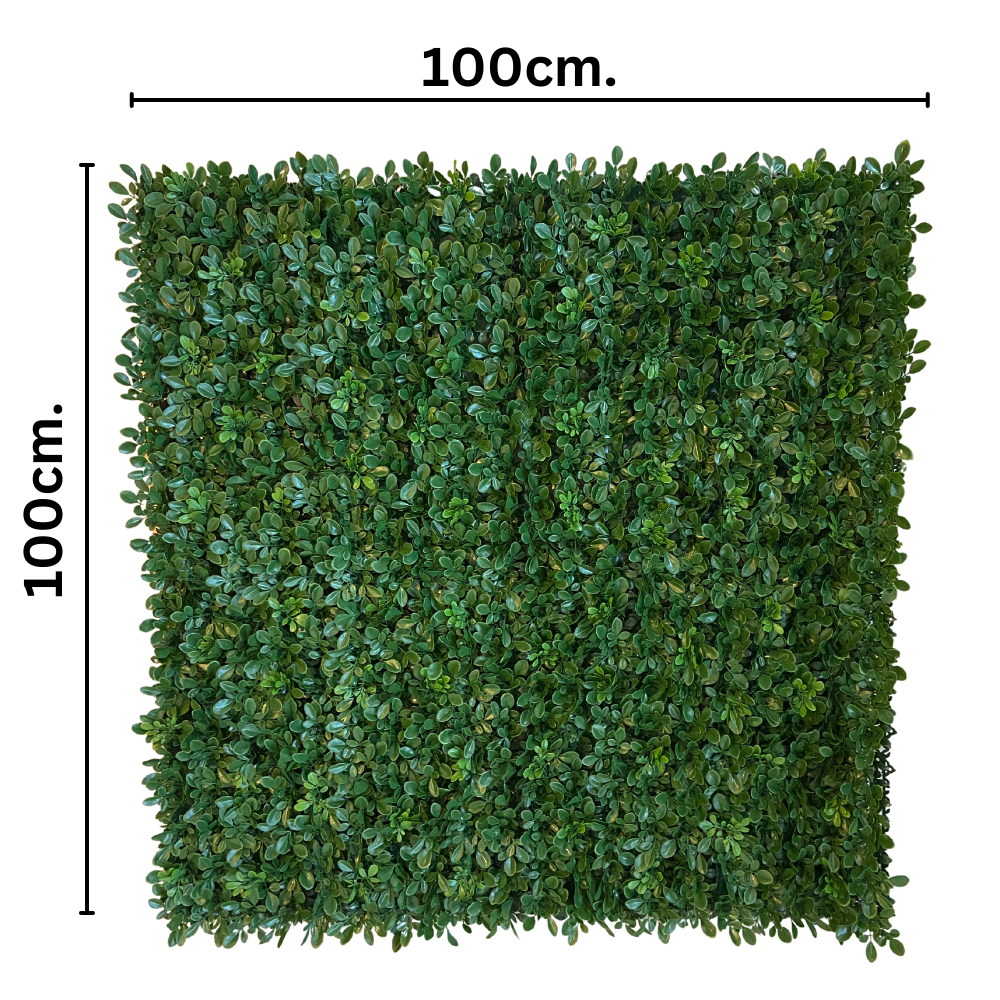

Verdevip Siepe Artificiale per Balconi in Rotolo da 1x3 mt (3mq) Rete Frangivista Ombreggiante con Foglie Finte per Arredo Decorativo Esterni Recinzione Ringhiera Giardino : Amazon.it: Fai da te

Foglie Bamboo H 90 ramo artificiale - Sconti per Fioristi e Aziende - San Michele di Ganzaria (Catania)

DASTY Italy Spa sceglie BM™ Piante Artificiali per arredare la Hall d'ingresso della nuova sede a Perdendo (BG). – BM Luxury® Piante & Giardini Verticali Artificiali LUX

10 Pacchi Mini Zucche Artificiali Finte con 500 Pezzi 10 Colori Foglie dAcero Realistiche Autunno Raccolta Caduta Realistica delle Foglie Colorate per Halloween Autunno Ringraziamento Decorazione Frutti artificiali Piante e fiori artificiali

STOOKI 2pcs Piante Finte da Interno Piante Artificiali Foglie Finte per Decorazioni Room Decoration Aesthetic per Pareti Di Nozze per Interni : Amazon.it: Casa e cucina

1 pezzo Gambi di eucalipto Foglie di eucalipto artificiali Steli Rami di foglie finte per l'home office Fiori Bouquet Centrotavola decoratoazione di nozze | SHEIN ITALIA

1 pezzo Ramo di foglie di piante artificiali, foglie di piante finte in plastica verde, per decorazione domestica | SHEIN ITALIA

1pc Foglie Di Ficus Rami Artificiali, Spray Per Piante Finte Verdi Per Arco Di Nozze Ghirlanda Fai Da Te Decorazioni Per La Casa | Acquista Su Temu E Inizia A Risparmiare

6 pezzi Gambi di eucalipto Foglie di eucalipto artificiali Steli Rami di foglie finte per l'home office Fiori Bouquet Centrotavola Decorazione di nozze | SHEIN ITALIA

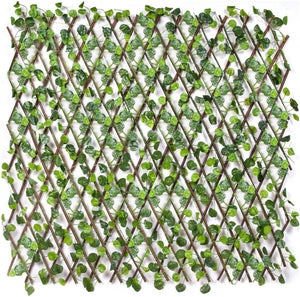

Siepe Artificiale Traliccio Legno Naturale Salice Estensibile Foglie Edera Finte 60x130 cm | Leroy Merlin

NUOVA REALIZZAZIONE A CASERTA by BM Luxury™ – BM Luxury® Piante & Giardini Verticali Artificiali LUX

SIEPE Finta Artificiale 1 x 3 metri Rotolo Rete Frangivista Frangivento Ornamentale con Foglia Osmantus Sintetica Anticaduta per Ringhiera Terrazzo Ba | Leroy Merlin

Mazzo Mazzettino Bouquet Di Rose Rosse Finte Con Foglie Regalo Per San Valentino - commercioVirtuoso.it

NIBESSER Edera Finta Cadente Pianta Finta da Interno 2 Pezzi Rampicante Artificiale Foglie Finte per Decorazioni Foglie Verdi Finte per Camera da Letto Giardino Parete Balcone(Anguria,2 Pezzi) : NIBESSER: Amazon.it: Casa e

Siepe Artificiale Traliccio Legno Naturale Salice Estensibile Foglie Edera Finte 60x130 cm | Leroy Merlin

3F Piante Artificiali - V - FILO EDERA - GHIRLANDA (UVR) - ALTEZZA CM 180 - UVR / 144 FOGLIE - 3F Piante Artificiali

6 pezzi Ramo di foglie artificiali, foglia di piante finte in plastica verde, per decorazione domestica | SHEIN ITALIA

Vendita online Piante Artificiali Verde verticale Milano Piante d'arredamento vendita on line piante artificiali Lugano alberi artificiali

Piante di steli di verde artificiale 70cm 120cm rami di foglie finte Ficus Twig felce cespugli verdi finti arbusti Home Party Wedding Decor - AliExpress

5 forchette foglie finte piante artificiali verdi amante lacrime succulente simulazione di vite appeso parete in

12 Foglie Tropicali Decorative,Foglie di Palma Artificiali,Foglie Finte per Decorazioni,Sottopiatti Foglia Verde,Sottopiatti Foglie,Tovagliette Palma,Tovagliette Foglia Sottopiatto,Tovaglietta Foglia : Amazon.it: Casa e cucina