Italia Live FM Radio: Listen Italian music, news, talk, sport radio stations & internet podcasts for Italiana by Phu Vang

Italia Live FM Radio: Listen Italian music, news, talk, sport radio stations & internet podcasts for Italiana by Phu Vang

Italo Disco USA radio online listen to disco funk and soul italian disco music by famous artists Miami, Florida BestRadio

Radio Italy - Radio Italy FM, Italian Radio Online to Listen to for Free on Telephone and Tablet:Amazon.co.jp:Appstore for Android

Radio Italia FM - Streaming and listen to live online music, news show and Italian charts musica from Italy Download

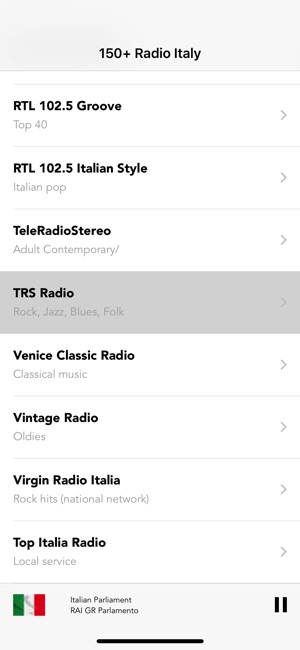

Italia Radio Live (Italia Radio, FM Italy Radios) - Include RAI Radiouno, Radio RAI, Virgin Radio Italia, RTL 102.5 FM, Radio 105, Radio Subasio | App Price Intelligence by Qonversion

Radio Italia FM - Streaming and listen to live online music, news show and Italian charts musica from Italy | App Price Intelligence by Qonversion